Kim Anderson’s drawings show anxiety, despair and environmental grief with exquisite detail

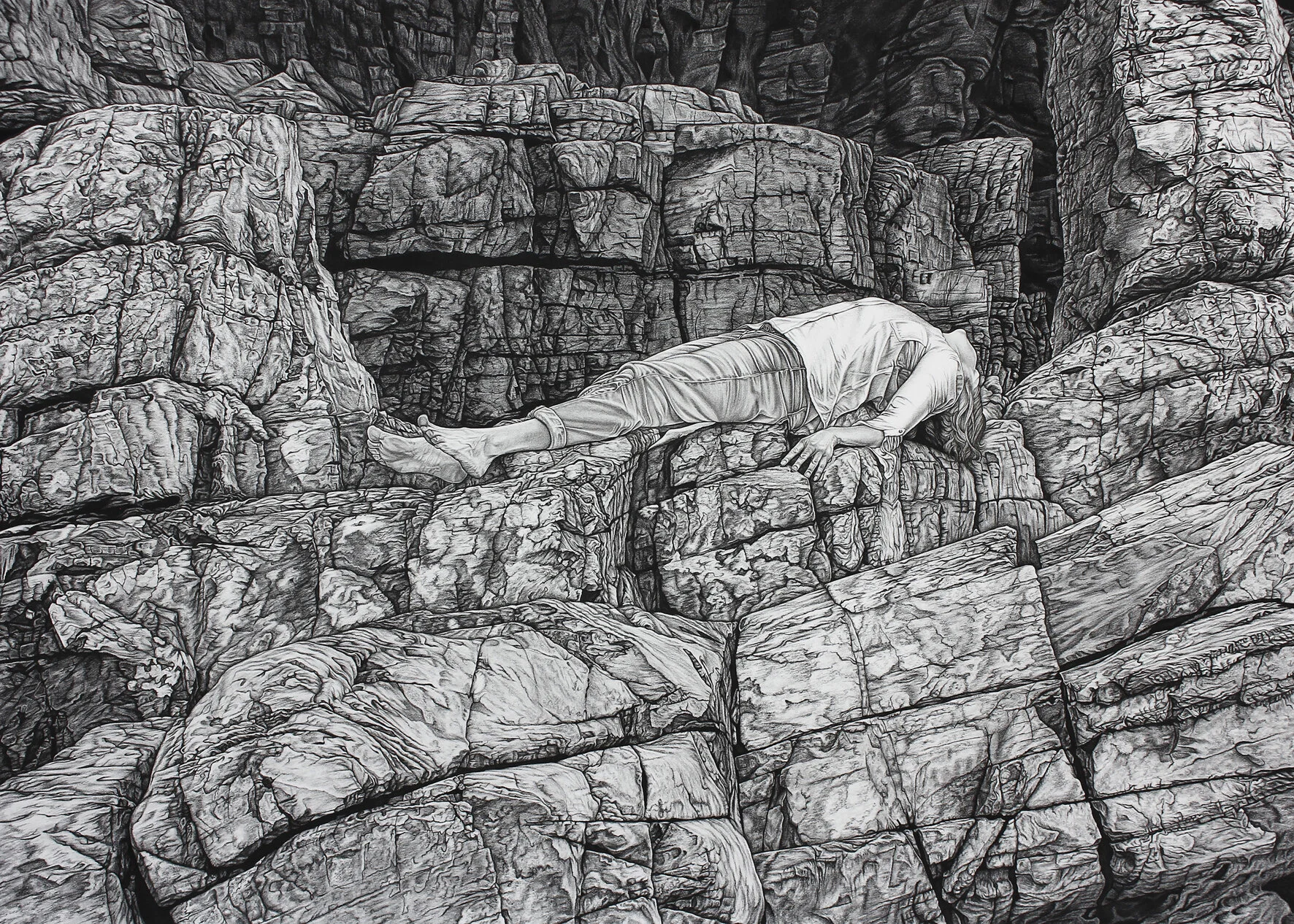

Away from the town and the tourists, it’s easy to feel overwhelmed at the expansive beauty of Scotland’s Isle of Skye. Here, among the green hills and cliffs that curve like ocean waves, Kim Anderson set up her shot. She positioned her camera and tripod nearby, clutched her remote control and lay still on some boulders.

To the odd tourist and dog-walker, she imagines things probably looked bizarre. But as part of Kim’s three-month residency in the Isle of Skye, Kim was photographing herself for a drawing she’d work on later.

“The Isle of Skye has this really wild, desolate beauty to the place, which I loved. It’s a tortured and wild landscape,” she told me in her Ballarat studio. “I spent a lot of time creeping around the landscape taking photos of myself.”

Shelter

Kim snuck a few rocks back to Ballarat from Skye, and she keeps the collection on a window sill in her studio. Beside it is an easel with the half-drawn artwork showing a figure lying on a rocky outcrop, lying with her knees squeezed to her chest.

Like this one, the figures in Kim’s canvases are often contorted into physical expressions of emotion – clenched fists, dangling arms, and foetal curls like this. She depicts forms of grief, anxiety and despair, with black lines from charcoal and ink pens and exquisite detail.

The drawings may be dark, but Kim’s studio is anything but, with sunlight brightening the white walls and exposed brick, even on the cloudy day we met. It perfectly befits Kim’s own sunny temperament, with her self-deprecating humour, quick laugh and quicker wit (I noted a human skull ornament on a mantel, and she told me it was the last journalist that visited for an interview).

“When I was ill, I realised that I only had one chance. That’s when I really decided to pursue my art practice. I thought, oh shit, I really only have one chance at life.”

In her mid-20s, Kim experienced anorexia, depression and anxiety, and “all the other mental health issues that come with that”. It was a pretty dark time, she says, and for many years her artwork exposed these sparking wires. But, she says, throwing her personal battles into art helped extinguish them.

Barry Humphries of Dame Edna fame bought this artwork in 2018, Conceal/Reveal, after seeing it displayed in a gallery on Collins Street.

“It’s this big scary cloud in your head, but as soon as you start articulating it, or writing it down or putting it into artwork, or whatever, then it becomes a bit more manageable,” Kim explains.

“We’re all worried about the stigma of mental health, but when people put it out there they get so much support these days. It’s great!”

On the canvas displayed in the studio, the mass of curls are a giveaway that the figure is Kim. When her artwork explored those tumultuous years, using herself as a model helped give the piece deeper meaning.

But back then, setting up shots was more like a Benny Hill skit than a serious meditation on emotion.

“That was in the days before I had a remote control. I was putting a self timer over the camera, and running in front of it, throwing a sheet over my head and then running back,” she says, laughing.

This piece, Timeless, was recently selected as a finalist in the Wyndham Art Prize.

Now, it’s more of a matter of convenience, and she uses a remote-controlled camera perched on a tripod. While her recent pieces still depict grief and anxiety, they have more to do with the environment and climate change.

“I was working a lot around personal grief, and it was starting to feel a bit too insular. You get tired of making work about yourself. I started to explore this concept of ecological grief – anxiety and grief in the face of climate change. In particular this theory of solastalgia.”

Coined by Australian environmental philosopher Glenn Albrecht, “solastalgia” describes the distress of witnessing environmental destruction close to home.

Or, as Albrecht writes for The Conversation in 2012: “I defined ‘solastalgia’ as an emplaced or existential melancholia experienced with the negative transformation (desolation) of a loved home environment.”

Solastalgia

This is what she explored in Isle of Skye, and in drawings of the Australian landscape near Mildura (exhibited at Flinders Lane Gallery). There, the landscape looks “apocalyptic”, with dried-out salt flats and protruding tree branches like clawing fingers.

Kim, as the model, wore an impractical ankle-length colonial dress and clung to the branches. In the drawing, her body mirrors the shape of the branches, and the folds and creases in her dress are like the ridges and clefts in the tree trunks.

“The Isle of Skye has this really wild, desolate beauty to the place, which I loved. It’s a tortured and wild landscape”

This performative aspect to her work, she says, probably comes from the 17 years she spent in ballet. This comes as no surprise to me given Kim’s ability to capture emotion through postures, and the subtle gracefulness she carries herself with. But would she ever return to dancing?

“No I don’t think I could now, but I still love it as an art form,” she explains. “I still find it really interesting, particularly with contemporary dance, how they continue to find new ways to express this stuff. That’s what I think is so important about art, we’re expressing things there’s no other way to express.”

Surrender

Despite using photographs of herself as a reference, Kim points out how she deliberately stops her work from looking photorealistic. It’s also one of the reasons why her artworks are in black and white.

She wants people to get up close and look at the abstraction of the marks on the canvas. Kim calls this detail imparted on trees and rocks their “language”, and this language is how her work appears so three-dimensional.

“It took me a while to find the right language with marks. At first I felt I was making the rocks from Skye look too soft and organic like trees.”

The language extends to flesh, too, especially in her large-scale drawings (her largest work on paper spanned 7.5 metres, and 10.5 metres on a wall), where, close-up, the lines etched in the surface of hands and feet make them look like landscapes.

“Hands and feet are the parts in contact with the world the most. That’s what I find interesting about them too. Your life is imprinted on those parts depending on what you do. You can read that in people’s hands,” she says.

She most enjoys drawing fabric – especially when she’s in the zone (which is also when she’s listening to a good true crime podcast). It’s a way she can evoke the feeling of hiding in plain sight.

“I suppose we all feel like we’re hiding in plain sight sometimes. You’re out there in the world and there’s all this stuff people don’t know. I think that’s what people are relating to, we’re all putting on the facade and pretending things are fine when maybe they’re not.”

“Hiding in plain sight” was actually the name of an exhibition she held in 2017 at 45 Downstairs that exposed her private journey through anorexia, scrutinising her own psychological trials.

The Penalty

“When I was ill, I realised that I only had one chance. That’s when I really decided to pursue my art practice. I thought, oh shit, I really only have one chance at life.”

Though, anyone who has battled a mental health issue knows these are battles long-fought – often it’s a matter of learning to live with the monster tapping on your shoulder, rather than exhausting yourself trying to fight it off. To explain, Kim recites a poem from Mary Oliver to me.

Someone I loved once gave me a box full of darkness. It took me years to understand that this too, was a gift.

Without that time, perhaps she wouldn’t have been so single-minded about pursuing art, she explains.

“Or maybe I’m just refusing to get a real job,” she adds, laughing.

Denial

And despite the deep personal roots, Kim says people have told her the artwork helps them make sense of their own personal battles, like listening to The Smiths when you’re already sad.

“One person who bought a piece said it reminded her of what she’d been through as a teenager. She said she saw a lot of hope in the piece.”

Recently, Kim has reached a turning point – she’s just turned 40.

“Turning 40 is kind of cool actually. I think with age, time and experience, you learn to cope with things a bit better. I have great days and really bad days.

“But other people will say, ‘40? Hey you’re a spring chicken!

“I recognise what’s going on now. Years ago, I didn’t. I’m kind of excited about my 40s, I feel like it’s a good age to be an artist.”